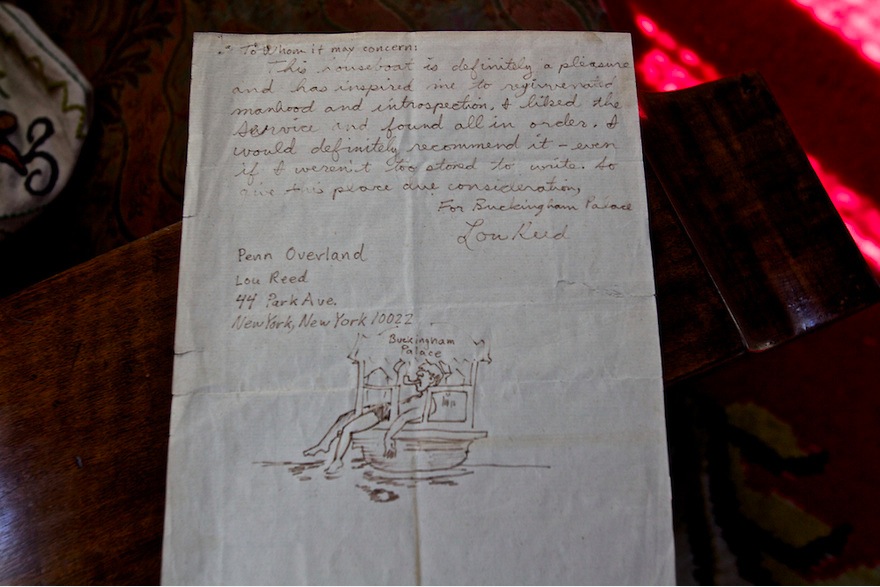

There was a time when these floating hotels that have rested on the lakes of Kashmir since the 1800s, were host to movie stars, artists, writers, famous musicians and wealthy western travellers searching for inspiration and tranquility. Lou Reed left a letter in the guestbook after his stay of one of the houseboats called Buckingham Palace, saying the floating hotel had inspired him to “regenerated manhood and introspection”, and that he would definitely recommend it even if he “weren’t too stoned to write to give this place due consideration”.

Today, the Buckingham Palace of Kashmir has seen better days. Along with countless other houseboats on the lakes of Srinagar, it is in desperate need of repairs as the wood is rotting. Built in the 1930s, Mr. Dunoo’s hotel was given the name by a loyal guest, a British lady who visited frequently for two and six months at a time. But that was a long time ago now. The romance of this watery paradise is slowly being overtaken by sadness from the loss of a golden era.

Lou Reed’s guest note, which Mr Dunoo’s grandson has been offered £100 for, but refuses to sell.

“Dinner is served on large, perfectly set walnut tables, and tea is sipped from small, delicate china teacups. Proprietors treat guests like royalty, cooking food and bringing refreshments.” (c) Helen Rimell

These hauntingly nostalgic images of empty houseboats, waiting for guests who may never come, were captured by photographer Helen Rimell, who traveled to Kashmir to document the floating ghosts of a tourism industry frozen in time– 1989 to be exact. It is the year that marks the almost overnight eradication of a thriving industry for the local houseboat owners and their ancestors before them, who built the floating inns more than 200 years ago.

It was the year that Kashmir fell into the grip of war between India and Pakistan, when armed insurgents advocating violent secession from India began the Kashmir Insurgency. With it came a total embargo on tourism– no more picnics by the lake in the moonlight, no more cricket matches, cinemas or alcohol.

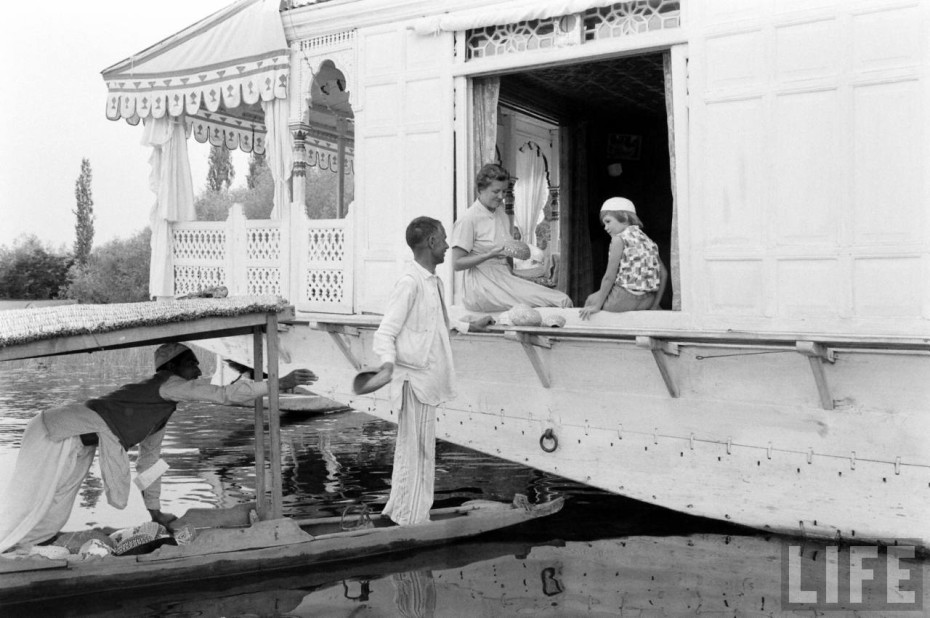

Kashmir in its golden era of tourism, shot by James Burke for Life Magazine…

No longer was anyone talking about Kashmir for its incredible beauty, its cuisine and handicrafts, or its triumphs in agriculture. The complexities of Kashmiri civilization just vanished. Reduced to a bloody conflict between the mosque and the army, for ten years in Kashmir, there were no tourists at all. Not a single one.

“An old radio sits silently, as there are no guests to play for…The views over the lakes were inspiration for many poets, artists and writers.” (c) Helen Rimell

Although thousands of people have died as a result of the turmoil in Kashmir, the conflict has become much less deadly in recent years. The European Union welcomed elections, calling it “free and fair” and congratulated India for its democratic system. Despite visitors slowly beginning to return, still the houseboats of Kashmir remain empty most of the year.

“The Butterfly Houseboat has a dining suite in mother of pearl … Before the political situation deteriated in 1989, many of the guests would stay for long periods of time and return frequently. Some of the guests gave presents to their hosts, including paintings and poetry. The bedrooms are themed, one bed is a lotus leaf, another a peacock, but the walkway is rotten and the western tourists no longer come.”

To make things worse, the Indian government is now threatening to close the boat hotels down altogether due to the pollution they claim they are causing to Dal and Nageen Lake. But according to the Houseboat Owners Association (HOA) in Kashmir, less than 12% of the pollution is attributed to their struggling industry.

Our photographer Helen Rimell was told that a vast amount of the pollution, which has now reached crisis point in Dal Lake, “comes from outside sources, such as the downtown area of Srinagar, where large sewage pipes empty waste directly into the lake”. There is a general feeling amongst the houseboat owners that because the tourism vanished and the pollution set in, nobody cares anymore and nobody wants to take care of the lakes.

“Mr Gulam Mohd Dunoo is in his mid 70’s, houseboats having been in his family since 1864. After the troubles began, a friend from England used to send him money, but it was not enough to survive, so his son would travel to India selling Kashmiri jewellery and carpets.”

“Every piece of furniture is intricately hand carved with patterns of flowers and leaves; colourful fabrics frame the windows, and dance gently in the breeze in narrow, wooden corridors”. Pictured below: The Mascot Houseboat.

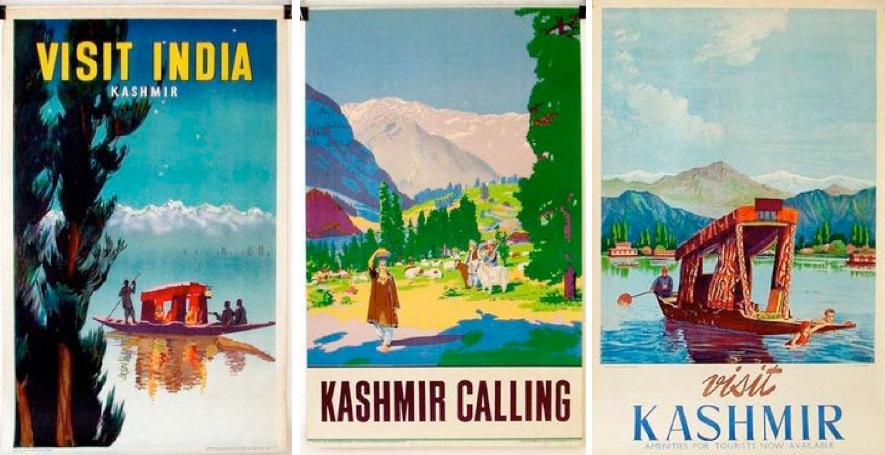

These antique houseboats were originally commissioned by the British, who owned them during colonial India. They became part of Kashmir’s heritage and many were purchased directly from British postmasters, traders and generals of the British Indian Army.

For generations, Kashmiri families have cared for these boats and welcomed western tourists onboard with unrivalled hospitality. Their guests became like friends and family, but now the memory of their faces is fading. The floating innkeepers pray for their return but are unsure they ever will.

One owner of a houseboat called The Flower Garden, Mr Abdul Karim Goosani still clings onto the proud memory of when actress Joanna Lumley, who was born in Kashmir, stayed for three weeks in the 80s on the boat his grandfather built.

Owners can’t afford to replace the rotting wood on the boats and walkways, but risk the looming fate of a watery grave if they don’t. Many houseboats have already been abandoned to sink into the lakes of Srinagar, leaving only 800 still afloat compared to the 3,500 houseboats recorded back in 1947. The suffering owners and their families are living in poverty, and if nothing changes, it’s believed the entire industry will disappear within the next twenty years. Their legacy, says Helen, “will only remain in books.”

Above, the Chairman of the Houseboat Association, Mr Azim Tuman, looks out across Nageen Lake from his boat, the Mascot. “If the houseboats die, a part of Kashmir will die with them.”

“The wind gently stirs through the trees, as the call to prayer sounds its melodies between the twilight and the darkness. The history and romance of the place is tangible, it hangs on every breath.”– Helen Rimell.

Staying on a Kashmir Houseboat

If you’re interested in following in the footsteps of Lou Reed or if helping to rediscover the forgotten places on this earth is your kinda thing, check out Mascot Houseboats – on their site you can even find scanned images of guestbook entries dating back to 1882.

Also featured in these photographs is Pride of Kashmir. And here’s a travel guide on how to choose the right houseboat for you.

Discover the full photostory of Kashmir’s Forgotten Houseboats.

For more Messy Nessy travel tips in India, see our India tips in the Destination Directory.